By Tim Gillespie

If You Are Going To Play In A Key Every Day, Shouldn't You Learn That Way?

Yes, you should!

Music is key based. You are always in one key or another. Always!

Yet playing a guitar is not taught that way! Why?

Once you understand keys and the chords and scales that come from keys, the whole world of music opens up before your eyes!

Suddenly everything is MUCH easier. And it totally makes sense when you get into it.

For $15, you can put this all to rest right now. Pick up a copy today.

eBooks are delivered instantly!

This is a column about exploring the fretboard of the guitar.

It will build on what was discussed the month before and truly get into working theory to produce new awareness. Today we are going to start an examination of keys. Almost every song played is in one key of the other. If you have a basic understanding of keys you can not only understand how music is made but how you can use this information to add to your music. To start with, there are only twelve different notes available on the guitar.

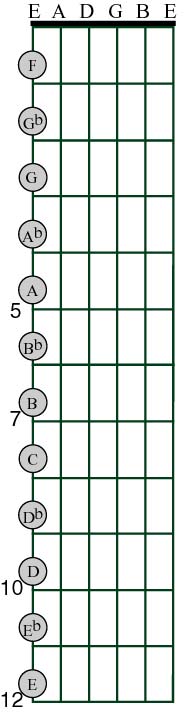

In the example to the right, they are shown on the low E string. No matter how hard you try to play more, there are only twelve notes on a standard guitar. They always flow alphabetically. When you get to the twelfth fret they repeat in order. Each one of these notes will create a key. Actually each note will create two keys. A major key and a minor key.

For instance, the note of C will become the keynote for the key of C major and the key of C minor. The same will be true of the other eleven notes. There are only twelve notes to create keys from. Each note creates two key for a total of 24 keys. These are called diatonic keys. They are also referred to as western keys (as in western music).

Each key will have a key note. The key of C will use C as a key note. Each key will use seven of the twelve notes available. A diatonic key splits the twelve notes into seven positions. There are only seven notes in any diatonic key. All diatonic keys are constructed the exact same way. They all have the same spacing of notes. It is the exact spacing that keys must adhere to. This spacing sets up the relationships inside a key.

So here is how you determine the spacing. If you move one fret, it is a half step or a semitone. A half step is the smallest distance you can travel on a guitar. Moving two frets is called a whole step or a tone. In my books, I use whole and half steps and I refer to them as WS = Whole Step and HS= Half Step. The exact spacing for every diatonic key starting with the keynote is WS, WS, HS, WS, WS, WS, HS (see diagram below).

If you start with the keynote and call it the first degree and proceed through all seven degrees of the key using this spacing, you will create a diatonic key. A solid understand of tonal centers and complex harmonies depends on a complete structural foundation. Understanding the components of a key will support these goals.

Below is a diagram of the exact spacing for any diatonic key. The different degrees refer to the different notes in the key.

.

The big diagram to the right shows the exact spacing on

the fretboard. You can see each key is formed by using only notes that

adhere to this standard spacing. The other notes are discarded and we

are left with a series of notes that fall into place because of the spacing

of whole steps and half steps. Much of theory is going to be centered

around these notes and the spaces that are created. Using the formula

presented here, whole steps and half steps create this exact spacing.

Notice the first three degrees are separated by whole steps. There is

a minimal distance between the third and the fourth degrees (a half step).

The big diagram to the right shows the exact spacing on

the fretboard. You can see each key is formed by using only notes that

adhere to this standard spacing. The other notes are discarded and we

are left with a series of notes that fall into place because of the spacing

of whole steps and half steps. Much of theory is going to be centered

around these notes and the spaces that are created. Using the formula

presented here, whole steps and half steps create this exact spacing.

Notice the first three degrees are separated by whole steps. There is

a minimal distance between the third and the fourth degrees (a half step).

Notice the jump between notes from the fourth to the seventh degrees is three whole steps. And notice the seven note is very close to the tonic (or one) note. Tonic is another way of saying keynote. Being so close to the keynote is like trying to stay out of a black hole. A sense of urgency to resolve to the tonic note is so overwhelming, it seems the seventh note is very unstable. It is very common to experience trouble when getting to know the seventh note in a diatonic scale. You get drawn into the keynote because if you play these notes, they will create relationships that want to resolve to the tonic note.

No matter what key you are in, it will have this spacing

and these notes will resolve to the one or tonic note. The spacing of

notes resolves to the first degree (keynote). Did you notice after all

seven notes are placed, the process starts over again with the first degree?

Playing scales will reinforce what we are talking about.

No matter what key you are in, it will have this spacing

and these notes will resolve to the one or tonic note. The spacing of

notes resolves to the first degree (keynote). Did you notice after all

seven notes are placed, the process starts over again with the first degree?

Playing scales will reinforce what we are talking about.

Here are a couple of concepts that are harder to see. Notice the fourth degree is five degrees away from the second octave (the one after the seven). And the five note is four degrees higher than the one note. The fourth and fifth degrees in a major scale have a lot of interplay and they form a very powerful force in a key. They both form major chords in a diatonic key. They are both four or five degrees away from tonic no matter how you look at it. Make sure you see there are two instances of the one note.

Ok, so we have some notes with this special spacing. So what? Of course you can see that these notes form the scale of the key. This is how the key is defined. It is defined by the scale. And since the key is defined by the scale, then the chords in the key are also defined by the scale. Each one of these notes will define one basic chord. And they will always be in the exact same order, because they use these notes which (as you know) are also in a very exact order.

The chords in a major key will always be in this order.

This is the reason why chords in a key are always in this same arrangement. The order of the notes in the key causes chords to be constructed this exact way.

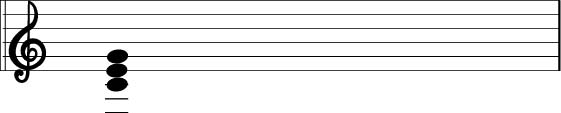

In this diagram we are starting each string with a note in the key of C. We are building a chord by using every other note, starting with the note of the chord, until we have three notes. Use the gray notes.

Notice it is the third degree that determines if a chord is major, minor or diminished. Refer to the box above to determine which is which. The diminished chord is also determined by the placement of the fifth.

Notice this. The C major chord has two thirds in it. A third is an interval using a one and a three note. A third refers to distance. Traveling from a three note to a five note is also traveling a third. In this chord the thirds are C to E, and E to G. The spacing determines if the third is a major or a minor third. The C chord is major because it has a minor third stacked on top of a major third. C to E is a major third. E to G is a minor third. The rule is a minor third stacked on top of a major third creates a major chord. A major third stacked on top of a minor third creates a minor chord. Two minor thirds together form a diminished chord.

This is the basics of keys. The key starts with the scale and the scale creates the chords. Now we have a complex set of notes to play against one another, and in the process we get to know the personalities of each degree in the scale. There is more to know. We have not even talked about the relative minor.

The relative minor is identical to the related major and

these notes and chords all belong to the relative minor as well. That

is why I say there is no difference between the relative minor (natural)

and the relative major. But that is for later. Just like chord extensions

are. For now, look at the twelve notes and notice the guitar repeats at

the twelfth fret. Visualize a key forming off each note. A key that uses

the exact spacing that we have been using. Now think about this series

of notes, each spinning a chord that fits into a family of chords. Now

think about twelve of these keys acting in complete unison. Pretty cool

isn't it! This simple lesson will set the stage for very complex uses

of these rules, stay tuned.

The relative minor is identical to the related major and

these notes and chords all belong to the relative minor as well. That

is why I say there is no difference between the relative minor (natural)

and the relative major. But that is for later. Just like chord extensions

are. For now, look at the twelve notes and notice the guitar repeats at

the twelfth fret. Visualize a key forming off each note. A key that uses

the exact spacing that we have been using. Now think about this series

of notes, each spinning a chord that fits into a family of chords. Now

think about twelve of these keys acting in complete unison. Pretty cool

isn't it! This simple lesson will set the stage for very complex uses

of these rules, stay tuned.

But this is just for starters. What about people that already know a few scales or maybe more?

You can take this information we have discussed so far and apply it to the entire fretboard and fully outline the playground. That is exactly what is presented here. If you are just beginning, do not worry too much about this right now.

The first diagram mapped out the low E string. Here is a diagram mapping out all six strings and twelve frets. This is positioned for the key of C major and A minor.

Any scale known to man for the key of C major and A minor natural can be found right in this diagram. Every one! No exceptions!

You might ask how every one can be in here if this diagram only goes up to the twelfth fret. We know the key of C is present above the twelfth fret. So how can everything be in here?

Remember that this entire twelve fret pattern repeats at the twelfth fret. If you play a scale between the 13th and 15th frets, it is the exact same scale as between the first and third frets. Check and see for yourself.

All we have done is apply the simple rules to the entire fretboard. For now think of any scale in either key and see if you can find it here.

Notice that the exact same notes in the key of C are used in this diagram. Also notice the notes use the exact same spacing as the rules dictate. Each string uses each note used only once.

Let me repeat this. Every diatonic scale for the entire key of C and A minor natural is in here.