If You Are Going To Play In A Key Every Day, Shouldn't You Learn That Way?

Yes, you should!

Music is key based. You are always in one key or another. Always!

Yet playing a guitar is not taught that way! Why?

Once you understand keys and the chords and scales that come from keys, the whole world of music opens up before your eyes!

Suddenly everything is MUCH easier. And it totally makes sense when you get into it.

For $15, you can put this all to rest right now. Pick up a copy today.

eBooks are delivered instantly!

By Tim Gillespie

How often do you talk about this subject? I bet not very often! There are lots of guitarists that use keys every time they play. Actually most guitarists use them every time they play. They construct chord progressions based on tonal centers and they construct lead lines to play over progressions. When they think about playing or learning songs, keys are one of the most important tools they have to help them understand what they are hearing and connect with the song.

But those thought processes generally are confined to their head. They are not generally communicated and much of the information is simply used and taken for granted. This become obvious when a seasoned musician tries to communicate the concepts to a beginner. Where do you start. There is so much background information that is necessary to know before the idea of controlling a key can be discussed. So they don't or they keep the subject simple for the sake of conversation. Usually.

When I started to play the guitar, I would investigate all sorts of stuff. Many times I would understand 80% of a subject but there would almost always be some concepts that remained disconnected and that caused me to not fully understand some very important details. It was only when I unlocked all the information that things usually began to fall into place. But the process of learning this all by yourself is difficult. If only someone would have taken me aside and explained some of the underlying principles, I could have gone much farther much quicker. That is what I hope to do today.

But before we look at relationships inside a key, let's review some aspects of keys we have already discussed.

Each key has seven notes. These seven notes make up the total sum parts of the key. Learn the notes and you know the key.

There are twelve notes available but we are going to pick seven. There are twelve possible notes you can play. Together they represent the chromatic scale. But we are interested in the diatonic scale. Diatonic keys split the twelve available notes into seven positions. These seven notes will have a spacing common to all diatonic scales.

Each letter of the alphabet is used once for the letters A through G. You may see an H substituted for the B note from time to time, but we are going to use A, B, C, D, E, F and G. As a matter of fact these are the exact notes we will use.

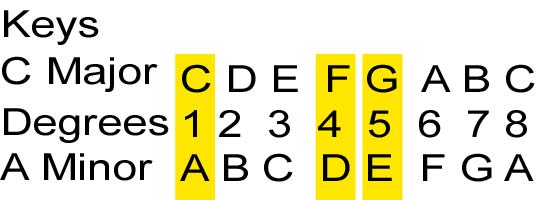

These notes construct the keys of C major and A minor. As we get into this, we will discuss both keys. Keep in mind these notes will occur in a variety of places over the fretboard. Anytime you encounter these notes you are dealing with the keys of C major and A minor.

Here are two sets of notes on the E strings. Notice the lower E string

(left) has all the notes available. In other words the Chromatic scale.

Here are two sets of notes on the E strings. Notice the lower E string

(left) has all the notes available. In other words the Chromatic scale.

Notice the high E string has only the notes of the key of C. C, D, E, F, G, A and B. This progression starts with the open E note and proceeds alphabetically. In twelve frets it will start to repeat.

The reason why these notes form a key is because of the spacing of the notes.

Look at the graphic, Intervals of a Diatonic Key, to the right. Starting at the first note and proceeding through all seven notes in the key, you get this exact sequence of spaces between the notes in every key!

Whole step, Whole step, Half step, Whole step, Whole step, Whole step, half step. Then the first note starts again. Look at the graphic. If you set it up this way, the result is every key will revolve around the tonic note. Whatever note you do this with will form a key. It just so happens that there are twelve notes and twelve major keys. It is the spacing that makes this work. This is why all the keys work the same way and why they all have this spacing. The spacing sets up this relationship. This is important because we want to look at the different personalities of each chord. Each one will have a personality.

But again I ask myself where do I start and how much do I communicate. There is a lot of information that can be examined and commented on. But I think it is best to bring it on, a little at a time. This way, there is time to think about it and experiment with it. That in itself should start the process of seeing keys and their relationships.

If you look at any diatonic key, you will see they all have this exact spacing. Look at any part of the fretboard when any diatonic key is expressed and you will see this telltale spacing of notes. Whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, whole step, half step.

I find it amazing that the people that designed and invented the guitar, knew this. This concept more than any other concept in my opinion, is the underlying reason why the fretboard is designed the way it is. The design is to accommodate these principles.

OK we have covered most of that before but it is important and worth a little review.

The Key of C Major

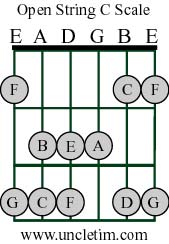

The Key of C MajorSo now we have the key of C. The notes are C, D, E, F, G, A and B. On the fretboard, using the first few frets, you can diagram their location and come up with the simple scale.

Here it is, the C scale. Play this scale up and down for the full range and then stop on a C note. Notice it brings the piece to rest. Now do it again but stop on the A note. It also brings the passage to rest but not as noticeably as the C note. There are two tonal centers here and they both revolve around the same spacing of notes. They form the two tonal centers C major and A minor.

Today you will start to see why they both work and how to use them.

But there is a difference between the two keys.

The spacing between the notes stays the same, but the scales start with different notes. That means they start at different places in the spacing. Here is an example.

The key of C Major.

C, D, E, F, G, A and B.

(C to D) whole step, (D to E) whole step, (E to F) half step, (F to G) whole step, (G to A) whole step, (A to B) whole step, (B to C) half step.

The key of A minor.

(A to B) Whole step, (B to C) half step, (C to D) whole step, (D to E) whole step, (E to F) half step, (F to G) whole step, (G to A) whole step. So the progression for A minor then becomes whole step, half step, whole step, whole step, half step, whole step, whole step. We are using the same spacing, now we are starting on a different note.

This is actually the Aeolian mode of the key of C. In other words we are playing the C scale but we are starting on the A note. The reason we are going so far into scales is because the personalities of chords occurs because of the spacing of notes.

The important thing to get out of this is this. The tonal centers are located at the first note (C) and the sixth note (A).

To really see the relationships inside a key, I find that notation has certain benefits. You may not like reading notes, but this is different. You really don't have to read music to observe what we need here, just look at the spacing of notes. And I have put the note right inside the symbol so we can see the notes at a glance.

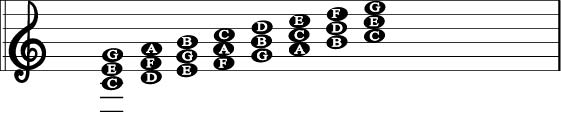

These are the notes of the key of C major. Notice the notes are C, D, E, F, G, A, B and C.

See how they proceed right up the staff. The notes proceed alphabetically.

Now take a look at what happens when we build the basic chords for these notes of the scale. The bottom note is the root note. It is the note of the chord.

Notice the chords are all built the same way. They are all constructed by stacking notes on top of the root note.

The first chord is C major (C, E, G). The next chord is D minor (D, F A).

Here is a diagram of the notes in the key of C major too. If you compare these two methods of describing the chords of C major, you will start to see the similarities. The gray notes are the notes shown above.

These different chords have names, like C major or E minor. But you can also describe them as chords built on degrees in the key. The first degree is C, the third degree is E. The seventh degree of the scale is B.

Notice this! The yellow box shows the scale. Each note in the scale is labeled as a degree. The pink box below also talks of degrees but the names refer to the chords built on the degrees. So the chord built on the fifth degree is the dominant chord. Dominant in the key of C. If someone says play the dominant chord in the key of C, you would play the G major chord, assuming we are not talking about seventh chords.

So here are

the names of the chords built on the different degrees.

So here are

the names of the chords built on the different degrees.

1. Tonic is the keynote.

2. Right next to tonic is the supertonic(2nd degree) and subtonic (7th degree).

3. Midway between the dominant and tonic is the mediant degree (3rd degree).

4. Midway between the subdominant and tonic (climb up to tonic, not down) is the submediant (6th degree).

Every chord shares two notes with the chord two degrees away.

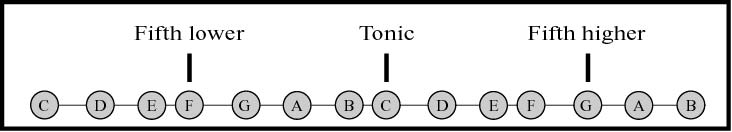

There are three major chords in any key. They are the first, fourth and fifth degrees. The fourth and fifth degrees are an equal distance from tonic. Look at this example to see this.

1. Look at the subdominant (F) and dominant (G) degrees. They are the farthest degrees from tonic. You have to look at the octaves of C to see this. If you go a fifth lower from C, you arrive at the subdominant (F). If you go a fifth higher from C you arrive at the dominant (G). They are both the same distance from tonic. They also both share one note with tonic.

Since these chords are so far from tonic, they are a powerful step away from tonic. They are major just like tonic, they share a note with tonic so there is some sympathy and they are the farthest distance from tonic in the key.

The progressions of tonic to fourth degree and tonic to fifth degree is probably the most often used movement. Rock and Roll could not exist without this move.

1. C major and F major both contain a C note.

2. C major and G major both contain a G note.

3. The tonic, subdominant and dominant chords are all major. C major, F major and G major.

4. Notice this! Every other chord contains the same two notes as the chord two degrees away. Look at all the yellow chords and notice the common notes. Then look at all the pink chords and notice all the common notes.

Note sharing is an obvious way a key will cause chords to relate to each other and progressions to cause movement.

When you play a one, four, five progression as shown, ( C major, F major and G major), in this instance you are climbing up the scale. The movement of the progression is up the scale. By climbing, you are establishing movement.

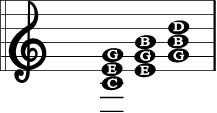

Notice these

chords all share the G note. Also notice the C major and E minor share

the E and G notes. And E minor and G major chords both contain the G and

B notes. The E minor is a combination of C major and G major. It is midway

between the two.

Notice these

chords all share the G note. Also notice the C major and E minor share

the E and G notes. And E minor and G major chords both contain the G and

B notes. The E minor is a combination of C major and G major. It is midway

between the two.

There are more relationships here than this and they are not confined to these basic chords either. For instance C major 7 contains the notes C, E, G and B (not shown). Notice the E, G and B notes are the notes of the E minor chord. So C major 7 contains the notes of E minor in it.

When you play C major and then E minor, you are using two of the notes in C major but you are also pulling the music up the scale by climbing up to the B note. This can cause movement up to the higher notes in the scale. In this example the whole chords are changing, but the motion could be just a single note.

So now you have movement away from tonic. But remember all these notes naturally resolve to tonic, so there will be a natural inclination to come back to tonic. Think of it as a rubber band stretching away to the farther ends and then snapping back. These chords suggest movement based on the interplay between notes, but they all want to lead to C and to a lesser extend to A.

Now lets look at the relationship between tonic and the subtonic. Tonic is C and the subtonic is B. So the scale proceeds like this. C, D, E, F, G, A, B and C . Notice as you pass B and proceed to C, these two notes are right next to each other. Between B and C is one half step. They are right next to each other. Now go back up to the diagram, Chords in the Key of C Major, above. Look at the B diminished chord. Notice there are two minor triads in it. Two minor triads form a diminished chord. That is why a diminished chord is formed for the B note in the scale of C major. It is important to note a diminished chord is very unstable. When you play it, it sounds awkward. It has a very unstable sound and for a good reason. Two minor triads creates a very unstable triad. It is the only basic chord in the key that is not built on a perfect fifth.

Now think about the pull that C major has on this diminished chord. Remember all these chords relate to C major. As long as we are just playing these notes they will all resolve to the C note or chord. And now right next to C major we have this very unstable chord. There is so much natural tension in this diminished chord and it is so close to tonic, that tonic acts as a magnet attracting the progression right to it. There is huge tension in a diminished chord that lives right next to tonic. It is very hard for a progression in the key of C to pass through B diminished and not suggest resolution by then achieving tonic. The hard part about this chord is managing the sound. It is easy for the tension to be overwhelming and bring unintentional results to the progression.

This is really fascinating. The minor chords function as a part of the key of C major. But they also do something else, they are the prime players in the relative minor key. In other words, the key of A minor relies on these chords just as the key of C major relies on the dominant and subdominant chords. Look at this graphic of the key of C major and A minor to compare the two keys.

See they act the same way the major chords act with the C chord. They are both the same distance from A. All three chords are minor. They are the primary chords for the key of A minor, just as F major and G major are the primary chords for C major. Notice both E minor and D minor both share a note with A minor.

There is one ore interesting aspect of the Sixth degree, the submediant chord. It is the relative minor to C major. It acts like a natural trap door. Say you are making up a progression in C major. Then you start moving to the A minor chord. You can structure the song to start revolving around the A minor chord and key by using the same chords. You can in effect steal the emphasis from the major tonal center and reconstruct it around the minor tonal center. You can stay in this new tonal center or you can modify it by playing the harmonic version of these chords. This is a drastic change but when done in a cleaver jazzy way, it can be quite interesting. The minor tonal center acted like a trap door and the melody went right thought it.

We skipped around a little but this should provide some thoughts for you to explore. This type of application of theory can be daunting at first. It can become easier when you play the chords and hear the relationships. But it will grow as you listen and play arrangements.

These concepts should start you down the path to understanding keys and

the mechanisms inside of keys. There are many more concepts we did not

discuss here. I thought this would give you something to think about and

experiment with. Just remember that a key is a collection of notes that

all revolve around a common tonal center. These notes, because of their

spacing act the same from key to key. If you begin to understand the reasons

why, you can exert control over the component parts. Don't forget to check

out "The Need For Speed". You will find exercises that will

help you hear the personalities in the key.